Organist James Welch in recital, sponsored by UCSB Dept. of Music. At UCSB’s Lotte Lehman Concert Hall on Friday, January 10, 7:30 pm.

When you order a new car with “all the bells and whistles”, recognized or not you have torn a page from pipe organ history. Mighty theater organs like The Wonder Morton housed at the Arlington Theater—great symphonic machines built during the silent movie era—not only blow ten thousand pipes, but also shake and whirl a host of special effects like sleigh bells and train whistles. With the Early Music Revival of the mid-Twentieth Century, and its hunger for “authentic” instruments and styles, a lean Neo-Baroque sensibility prevailed in the pipe organ world, and with it a retreat from the electronic advantages of modern engineering, and entertainment culture excesses.

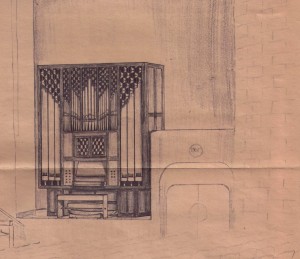

It comes as no surprise then, that when designs were considered in the late 1960’s for a UCSB campus pipe organ to be installed in the newly planned Lotte Lehmann Concert Hall, the academic currents of the time prevailed, and a mechanical action organ made by Dutch manufacturer Flentrop was chosen. “These are organs that were built—that are built, this company is still in business— in the old style, the way that organs were always built before electricity,“ internationally acclaimed organist and scholar James Welch told me by phone last week. Rather than using electronic servos or pneumatics to control the air flow into the pipes, so-called ‘tracker’ organs put the player solidly in touch with the valves. “The trackers are connecting rods that go between the keys and the valves that let the air into the pipes,” Welch explained. “It’s an organ that if Bach were to walk in himself and sit down, he’d say, ‘Oh yeah, sure, this is what I know.’”

1971 Sketch for proposed Flentrop Organ placement in Lotte Lehman

UC Berkeley organist Lawrence Moe performed the inaugural recital in 1972. Meanwhile, Welch was pursuing a Doctor of Musical Arts degree in organ performance from Stanford University. In 1977 he was offered the job of Adjunct Professor and Lecturer in Organ at UCSB, a position he held for 16 years. During his tenure, Welch performed at least 25 recitals on the Flentrop organ, and sponsored regular recitals by his students. But Welch’s departure in 1993 marked the suspension of active life for the Flentrop. No one knew the instrument so well, and few have known it since. With a dwindling of Music Department interest and funds (and no Sunday service to keep its bellows regularly inspired—as would be the case for a campus chapel organ) the instrument has languished half its life largely unused.

Friday night Welch returns to the keys, stops and trackers of the formidable Flentrop—his first recital on the instrument since 1997—for a slightly tardy 40th anniversary performance. The occasion, co-sponsored by The American Guild of Organists, will also include a lecture by Occidental College professor and UCSB alumnus Edmond Johnson, who will speak on the legacy of UCSB’s legendary musicologist, Karl Geiringer. Expect a tantalizing, varied and solid program of J.S. Bach and California composers that leaves all bells and whistles behind.